Junior Year

My parents and I spent five months going to every different doctor imaginable, but none of them could diagnose what I was experiencing. I was usually listed as “other.” It wasn’t until January 2022, when Stanford’s Dr. Michelle Monje published an article in Apple News, that we figured out I had Long Covid. When I returned to school for my second junior year, I came back to a community of people who had no idea what I experienced. I feel compelled to use my photographic ability to express what it felt like having Long Covid. I want to be for others what Dr. Monje’s work was for me: an explanation of what I went through.

“Memories are what our reason is based upon.”

My memory of dealing with Long Covid combined with post-concussive symptoms is scattered at best. I was overwhelmed with raging headaches, nausea, migraines, and insomnia. My eyes couldn’t focus. Overstimulated by everyday sights, my visual speed and comprehension decreased by 60%. Everything I saw brought sharp pain, and the sharpness sent my eyes sprinting away from the confusion associated with everyday life. Every scene I saw appeared too busy for me to focus on one thing. I longed for order among the chaos. Connections in my brain stopped working. I could no longer associate emotions with the events occurring in my life. I felt flat and unrelatable. Because memories are tied to emotions, my mind is busy but blank. I don’t remember anything without a photographic aid. My experience with this new disability of Long Covid is unprecedented, and so is my mental composition. My memories don’t exist in my mind; they exist in my camera roll. I used my experience relearning how to see as a lens to view this project. These photos are my memory of how I overcame Long Covid. Through these images, I aim to unlock the details of my story, so others can explore, understand, and empathize with my Long Covid experience.

“If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs, and blaming it on you,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss”

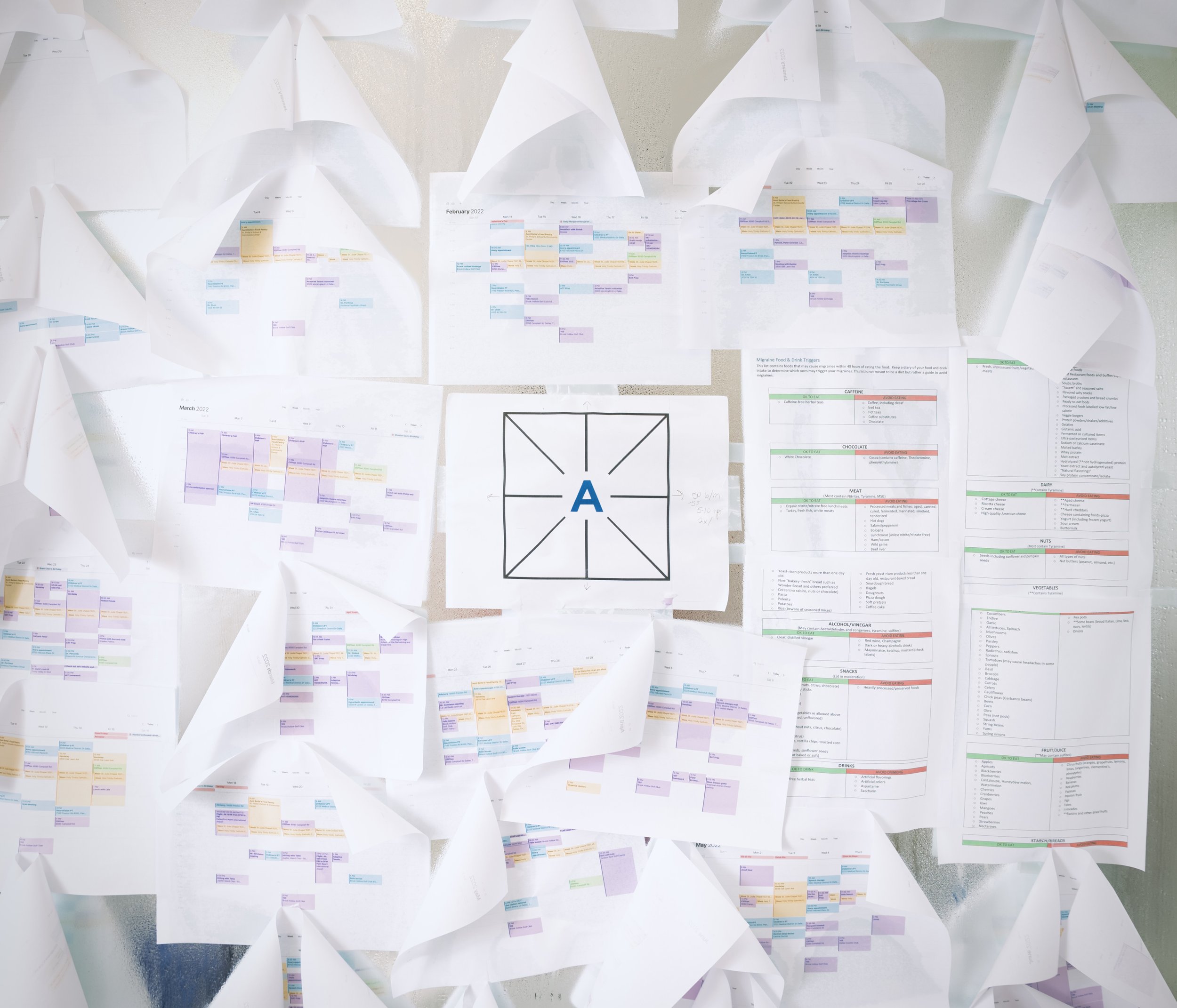

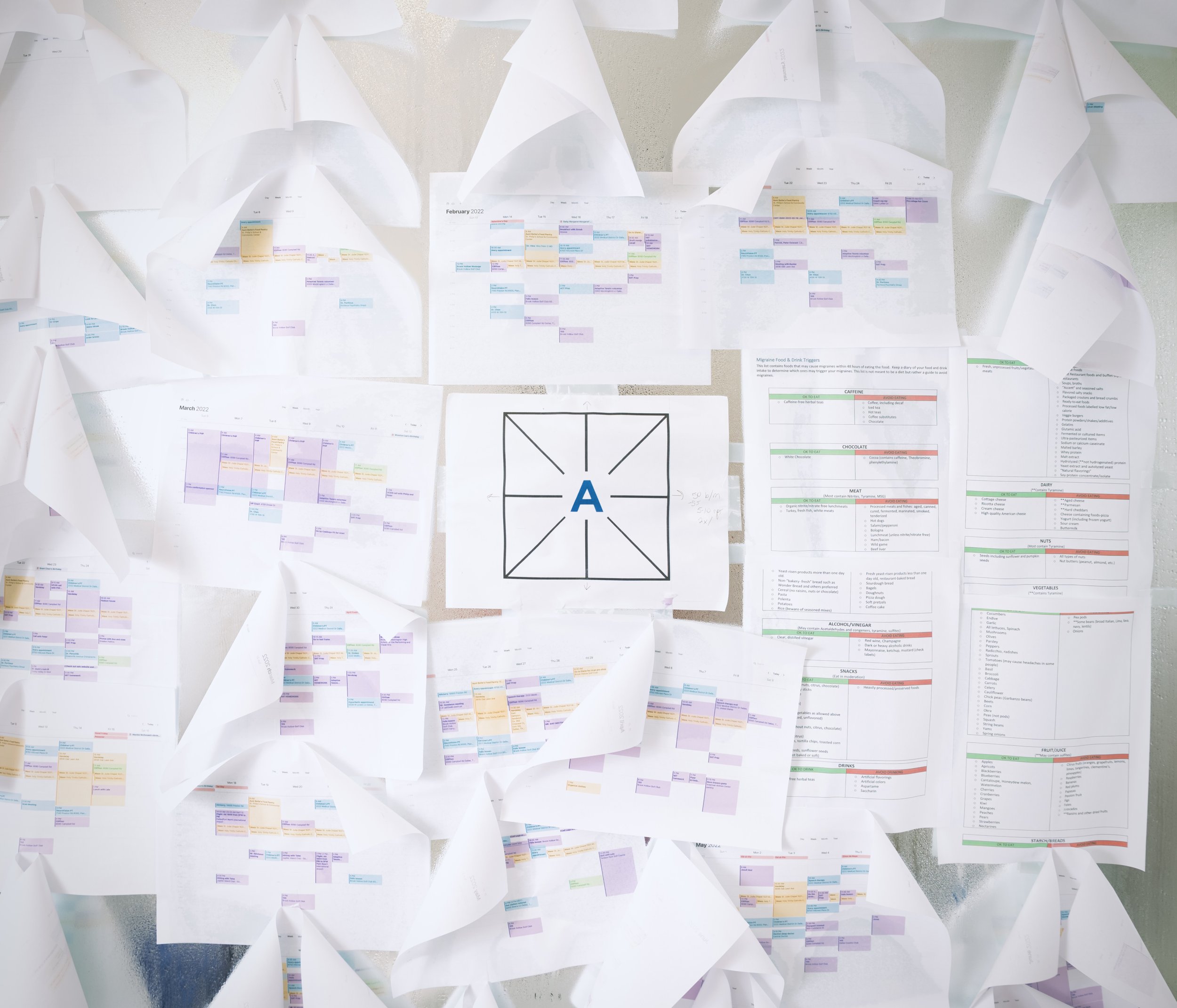

While suffering from Long Covid, I experienced severe memory loss. Recovery starts small. The simple question of “How was your day?” became impossible to answer. I went to speech therapy for three months to learn how to answer questions with something other than a blank stare. I learned to write everything down to remember it. I kept a journal of every activity and how it affected my pain level. Every event became a careful study of what triggers or alleviates my headache. So much happened, but my brain remembers none of it; only my calendars do. I kept calendars on my bathroom wall to remember what had happened and was happening in the current and previous week. I taped up the second copy of my new dietary restrictions in the hope that I would remember it and not have to bring the papers with me everywhere. With so much happening and nothing registering, one constant centered me: recovery. The A is a physical therapy exercise designed to practice vestibular balance. As I shook my head back and forth and up and down and across the diagonals to the beat of a metronome, it made everything spin, except the A. It centered me. No matter how fast I move or how unclear everything is around me, the A is there, still, centered, begging me to recover.

“Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken”

Shopping became a form of torture. I returned from the doctor’s office with a list of vitamins and pills to purchase for daily consumption. When I entered the store, I was greeted by flickering fluorescent lights. I walked down the aisles head down without looking at any of the items. Nothing offered any comfort from the busy, bright, packed background of the shelves. I dashed in to focus on a single item, and waves shot back from the shelves, sending my brain into a screaming terror. Ten minutes later I tried again, this time with my eyes closed, reaching in and picking one bottle at a time. After blindly examining the entire shelf, I finally grabbed all twelve supplements I needed. I returned home in shock, still paralyzed from trying to focus my eyes on a single item in an array of distractions.

“And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’”

Concentrating on class material and interacting with people at school sent my brain into a spin. Every day after my last period class, I would hide in the bathroom and vomit. It helped release some of the pressure built up in my head. As the pain increased, my nausea got worse. Throwing up after school wasn’t enough. At night before going to sleep, the pain would boil over. I would sit in my car with the seat fully reclined and the AC on full blast for about an hour until the nausea subsided. On nights when I couldn’t freeze my stomach into submission, I would hurl chunks of pink Pepto Bismol tablets out from my throat and onto the floor. I had gone from being a nationally competitive athlete to being unable to run, breathe, or eat. In physical therapy, we found that after 3 minutes of walking at 3mph, my blood oxygen level fell to 78%. That number is equivalent to what climbers experience at Everest base camp. Any attempt at physical exertion resulted in another pool of vomit. To avoid migraines and keep things in my stomach, I adopted an extremely restrictive diet. It was an anti-inflammatory, anti-migraine, gluten free, “Tom Brady” diet. I ate fruits, seafood, and lots of fish. My nausea eventually went away, but its effects persist in the choices I make at every meal.

“If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone”

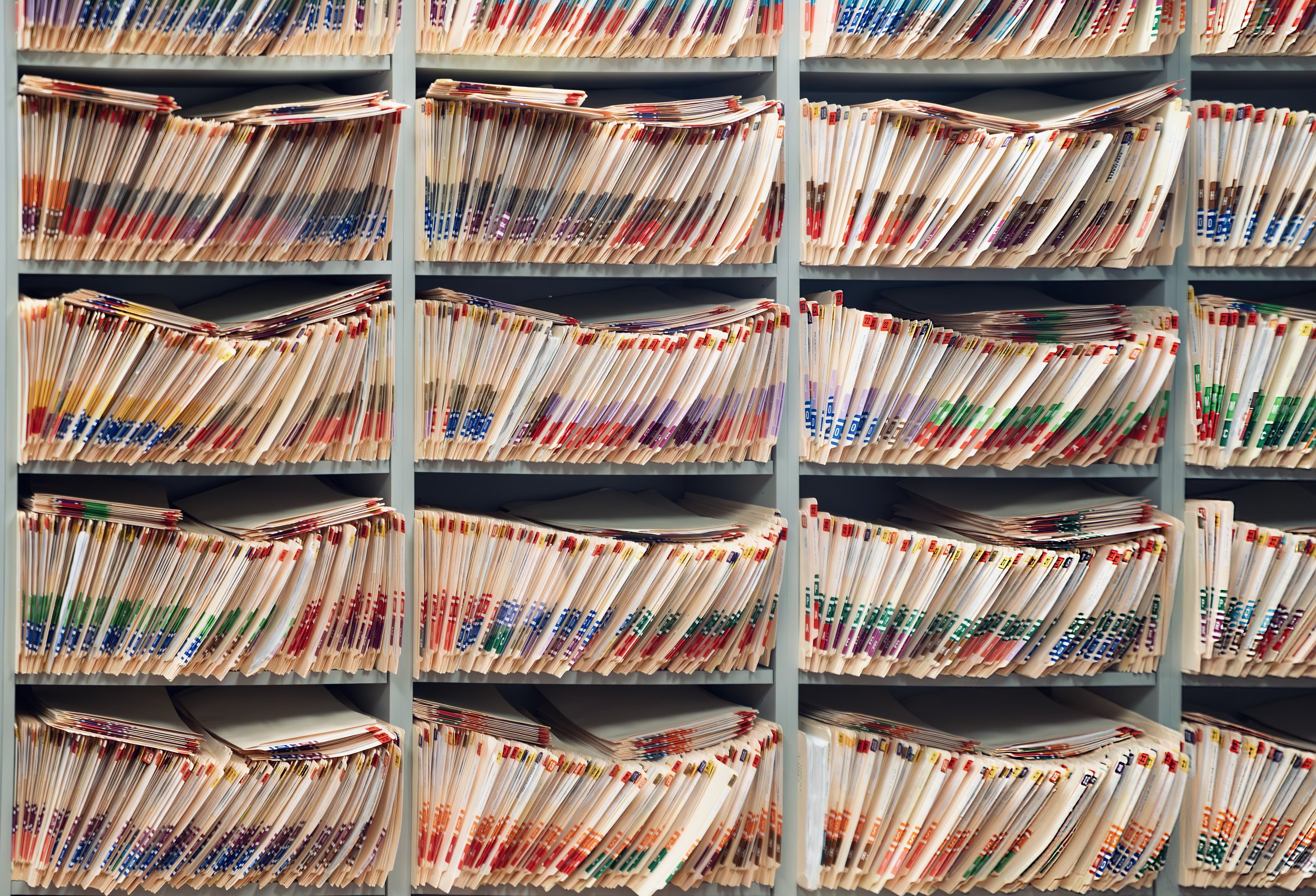

When I left school, the classroom was replaced by a doctor’s office. I created my schedule to mimic school. Different appointments resembled different class periods. Textbooks turned into appointment notes. Tests transitioned to recovery goals. These files are my classmates. When I was the only one out of school and recovering from Long Covid, I often thought, “Why me?”. Why should I be picked out from everyone else and be made to suffer alone? The manila folders, stacked alphabetically in an infinitely increasing pile, reminded me that I’m not entirely alone. There are people out there going through things just like me, and even though we will not meet, we will always share that bond. I feel a responsibility to open up my file and share every detail of my experience so my classmates in suffering know they are not alone.

“If you can wait and not be tired by waiting”

5 days a week for 8 months, I sat in a doctor’s waiting room. For the duration of every minute spent waiting, I would close my eyes. If I opened them, I risked constant mockery. In every single doctor’s office lies a plethora of magazines. They’re in the hands of people waiting for their yearly check-up, ripped apart by kids looking at the pictures, or sitting in a neatly sorted collection on a coffee table. The purpose of the magazines is to bring some sort of levity to an otherwise serious moment. For me, the magazines served as constant reminders that I couldn’t read. The words, titles, and bright covers humiliated me. The letters in their fancy fonts laughed at me, reminding me that if I try to read, my eyes will be sent into shock and my brain into frustration. In a doctor’s office, a place marked with dread, diagnosis, and anticipation, the one thing intended to bring comfort, the magazines, mocked my inability to read.

“If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too”

I entered into a partial hospitalization program while I was away from school. Because Long Covid is a new disease and data was only beginning to come out about its existence, teachers, friends, family, and even doctors were skeptical of what I was experiencing. So was my school. They wanted to make sure I wasn’t just making everything up. I faced the ultimatum of either never attending my school again or enrolling in a partial hospitalization program. A PHP is designed to protect kids who are a risk to themselves. The non-pc term is suicidal. For context, the next step up from a PHP is mandatory overnight hospitalization for an undetermined period of time until the doctors concur you are safe to interact in society. It’s important to clarify that I was never like that. I looked through the windows of the downtown building while imagining my friends running, thinking, and remembering at school, all things I could no longer do. Alienated, I served my sentence in the PHP, observing the weighted chairs, anonymous nurses, and security cameras. There were no phones, no pens, no surnames, and no personal conversation at “suicide school.” The glass separated me from the functional world, instead associating me with everyone else who needed help. No amount of physical pain could amount to the mental fear of capitulating to the fact that I will always have to view the world through a glass wall and know that I can’t touch but only see everyone else. I finished the month-long program in 6 days, and I returned to my school the following year.

“If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch”

For 19 months, I never traveled without my Oakley Radar EV Path or Sutro Lite sunglasses. Fake Pit Vipers, my friends called them. While struggling with Long Covid, I didn’t make eye contact with anyone. My eyes couldn’t focus for long enough to look at people. I wore sunglasses to hide my distant gaze and protect my sensitive brain from the excess movements and light. My inability to make eye contact defined my difficulty in relating to society while I had Long Covid. I stayed away from crowds at all times, and I put myself in positions where I wouldn’t have to interact socially. Compounding my social difficulties was my dependence on chemically altering medications. My doctors and I experimented with 15 different prescription drugs in my recovery process. They helped me feel less pain, but they also rendered me completely incapable of experiencing empathy. They numbed my senses to the point where I could no longer feel any emotions. Cormac McCarthy says, “the eyes are the window to the soul.” I wore reflective sunglasses, and in my soul, there was nothing to see. Medication had taken my personality. My sunglasses hid me from people, but also, in the face of everyone, they hid people from the struggle I was experiencing. They protected me from peering eyes and made me anonymous, another person in the crowd.

“If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run”

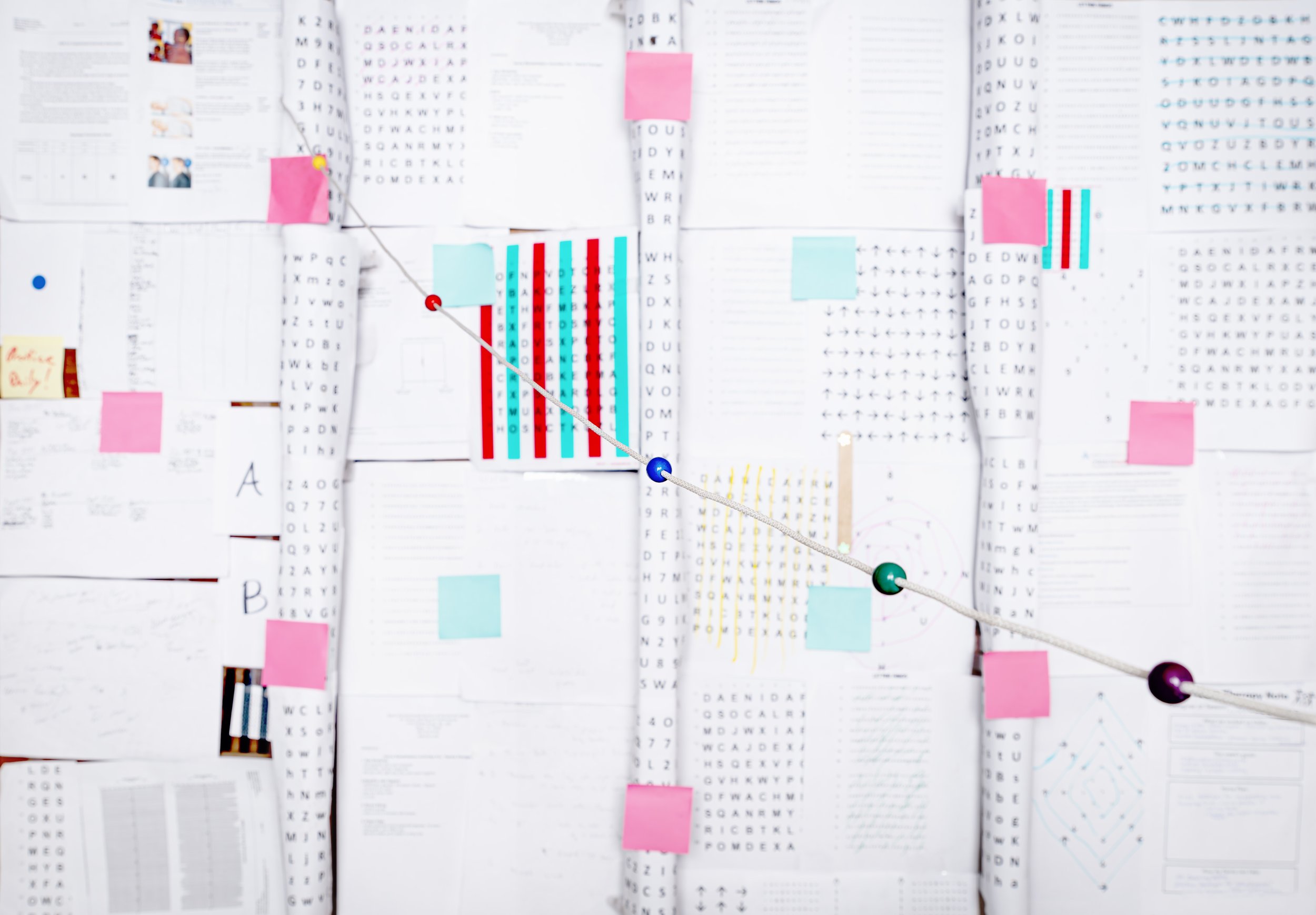

I completed 8 months of vision therapy by the time I returned to school. I did eye stretches with the popsicle stick, sticky note saccades, the near far chart, stab and say, MAR with an eyepatch, red/green flippers, 2 chart 2 wall, the lifesaver card, BAR with a polarized chart, barrel card, doorframe saccades, line jumps on paper, 3 strip saccades, and prism flips. Every drill had the goal of straining my eyes and their connection to my brain. Sticky note saccades trained my peripheral vision. Stab and say connected my sight to my mental recall. The Brock String trained my ability to focus and move my focus back and forth. I held one end of it to my nose and the other taped to a wall. As my eyes focus on one bead, the line of string diverges on either side of it to form an optical X. Amid this illusion, I gathered myself. The past and future can move in different directions, but the present must stay in focus. Complete recovery starts with putting my full focus into this one day, this one meal, this one minute, this one drill, and this one bead.

“If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same”

I have always built Legos. When I empty out the bags, they begin as disorganized clumps of pieces. Amid the confusion, I envision the potential. Legos have always acted as a time capsule for me. I order individual pieces that make up retired Lego sets I had when I was younger and rebuild them. Feeling a Lego in my hands and knowing exactly where every piece is placed sends me back to the time I built it. Holding my X-Wing Starfighter makes me feel the same joy and energy I felt when I was five. While recovering from Long Covid, my Legos took on a new meaning. They reminded me that no matter how broken, how sick, or how simply impossible the final creation appears, everything can be rebuilt. Whether it’s practicing my reading speed, relearning how to write, training my tennis to get back to a nationally competitive level, or even relearning how to breathe, I think of my Legos. They remind me of Marcus Aurelius. He often told himself, “exaleipsai phantasiai,” or “erase your impressions.” I’m challenged to view my own recovery process in the same way I view Lego pieces: without judgment. I don’t see Lego pieces as broken or scattered things that lack meaning, and therefore I should not see my "severely disabled” self as something negative. I have extreme potential and am yet to be rebuilt. Like a Lego, I can put the pieces together and build something great.

“If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you”

This one is the hardest to put into words. You know the feeling of watching your classmates jump into a pool as a class after their last day of high school as you observe, completely dry? Or the feeling you get watching them walk across the stage at graduation while you sit below them and watch? I do.

At St. Mark’s, seniors are marked by their blue shirts. Everyone else in grades 1-11 wears a white shirt. Entering junior year, my classmates and I expected to be in our last year of white shirts.

Since first grade, at age 6, we were taught St. Mark’s’ character and leadership initiative: The Path to Manhood. In Lower School, I learned to “work as hard and play as fair in Thy sight alone as if all the world saw.” In Middle School, I played junior tennis nationally, representing my school’s values of Courage and Honor across the country. Before junior year, my classmates elected me as Class of 2023 Grade Representative for student council. In my campaign speech, I said that “adversity is an opportunity,” and with me leading, our grade would be represented by that mindset. I was excited for a great junior year, my last of 11 years in a white shirt.

Then, at the start of August football training camp, I woke up with a raging headache. I moved to the floor because the contrast between the soft bed and the needles inside my head upset me. On the fifth day of repeating this routine, laying on the wooden floor, I briefly opened my eyes to see my mom crying, pleading with me to get up with nothing but pure fear in her eyes and in her heart. I hoped if I closed my eyes, the pain would subside, my mind could focus, and I could go to school. After weeks of Advil, acupuncture, stem, rest, and heat treatment, my pain only increased.

I spent the fall struggling, attempting to work but knowing I couldn’t keep up. In English, we had a 70 minute in-class essay. I could only write 9 sentences. I planned to spend winter break making up schoolwork. Instead, I slept as long as I could, knowing it was the only way to alleviate my nausea, brain fog, shortness of breath, insomnia, low energy, vision problems, and headaches. I tried desperately to remain in school, but with my health continuing to deteriorate, I eventually had to go on medical leave.

After spending 10½ years with the same class, I returned to my old school in a new grade. Reintegrating into classes while I still wasn’t fully healthy or functional, I was met with the social challenge of trying to find a place where I fit in. My old classmates were all seniors now, but I was still in a white shirt. My new classmates weren’t the guys I went to first grade with. They weren’t part of our undefeated flag football teams. They didn’t struggle with me through our 10-day freshman orientation camping trip, and they didn’t hang out with me during Covid lockdowns. I didn’t know them, and now, after being gone for a year and wearing a different shirt, it felt like my seniors didn’t know me. I had gone from being the official Grade Representative to not even being part of that grade.

Surrounded by people I could call my brothers, I felt completely isolated in my own school. I watched with my eyes forced open as I saw my grade experience their entire senior year without me. This was the hardest part of overcoming Long Covid; harder than breathing without working lungs. My white shirt represented all the pain I had to endure in the past year, and it served as an official marker that I will never be the same.

While recovering, I told myself that no good comes from dwelling on future pain. So, I didn’t allow myself to cry for the duration of my second junior year, from August until May. I understood that the day would come when my class was officially no longer at my school, so I didn’t let myself worry about it until that day finally arrived. On the night of graduation, I didn’t sleep. Neither did they. They stayed up partying all night while I let out a junior year's worth of tears from my eyes. That night about sums up the last year. My friends went one way while I experienced every pain imaginable on the other.

I’m reminded of a quote from Robert Frost. “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – I took the one less traveled by, / And that has made all the difference.” Frost’s poem originates from him taking walks with his friend Edward Thomas. At a divergence, Thomas would choose one path with the hope of finding something noteworthy along the trail. When he found nothing, Thomas would always lament not going the other way. I’m still learning to embrace the road I’ve taken. With every passing day, those painful memories drift farther and farther away, and the lessons I’ve learned from overcoming Long Covid become ever more solidified as a part of me.

My favorite part of Frost's poem is the last word: Difference. We don’t know whether that “difference” is positive or negative. I suppose we get to choose for ourselves. If you choose to see the difference as positive, if you view adversity as an opportunity, “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster and treat those two impostors just the same... then yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it, and—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son.” This journey is my Path to Manhood.

On the last day of school, seniors traditionally all take off their blue shirts, put the shirts on a statue, and jump in the pool. This year, every senior waited outside the doors because the pool was locked. Knowing a secret entrance to the natatorium, I walked in, unlocked the doors, and watched all 100 of my classmates run past me to jump in the pool after their last day of classes at St. Mark’s. I stood there paralyzed, shoes and socks off, ready to dive in and join them but unable to. The next day, on the morning of my first day of school without them, I took all 100 of my former classmates’ blue senior shirts from the statue, laid them out on the school tennis court, and made this photo. Facing the camera, my one white shirt is slightly above and left of the middle, positioned similar to where the heart would be on a human body. After the photo, I returned every shirt to the statue with the help of the new St. Mark’s administration and went to class, ready for my senior year.